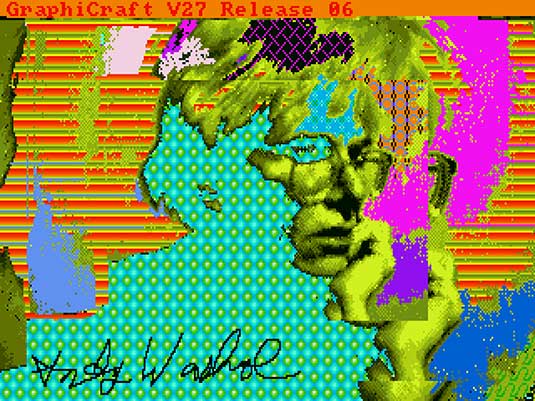

Never Before Seen Digital Works by Warhol Recovered

Friday 25th April 2014 Perhaps the most dreaded scourge of the digital artist is data loss. Unless you manage to regularly maintain a strict backup schedule to keep copies of all your digital work files in separate places (and let's be honest - that's right up there with flossing every day and jogging 4 times a week) you have probably encountered the problem before. But what happens when you diligently back up your work, only to have the storage medium you used go out of style? Imagine being a filmmaker who has copies of all their work on BetaMax tapes. Well, the same thing apparently happened to works by pioneering pop art icon Andy Warhol.

Perhaps the most dreaded scourge of the digital artist is data loss. Unless you manage to regularly maintain a strict backup schedule to keep copies of all your digital work files in separate places (and let's be honest - that's right up there with flossing every day and jogging 4 times a week) you have probably encountered the problem before. But what happens when you diligently back up your work, only to have the storage medium you used go out of style? Imagine being a filmmaker who has copies of all their work on BetaMax tapes. Well, the same thing apparently happened to works by pioneering pop art icon Andy Warhol.

Fast forward to 2014, when Cory Arcangel saw a Youtube video of Warhol promoting the Amiga 1000, which inspired him to reach out to the museum to find out what happened to his experiments with the first computer graphics systems. The result was a collaboration between The Warhol's chief archivist, Matt Wrbican, and a group of computer enthusiasts from Carnegie Mellon University, the CMU Computer Club. Thanks to the expertise of the CMU Computer Club, the images were able to be recovered after painstaking tests and careful problem solving. For those of you who've read our recent post on drawing tablets, you'll be easily able to see how even the most capable artists would have struggled to adapt to the mouse interface that was standard issue on most computer systems at the time!